On Friday, 13 February, students occupied the Bungehuis at the University van Amsterdam (UvA). By the end of the first day of the occupation the movement grew in support with around 200 people participating in the occupation. It lasted 12 days and during this time they held several student activities such as lectures and movie nights within the Bungehuis, despite having no access to the internet for the duration, and gas being cut off for the final few days.

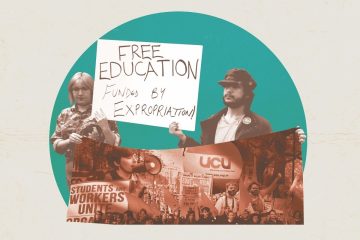

This occupation was in opposition to the de-democratization and privatization of the university at the expense of students and staff. Universities around the world are being administered based on market thinking. This takeover of higher education though a capitalist profit based agenda can be seen in the increased budget cuts in the arts and humanities. Student movements have started in several countries around Europe, such as the Free Education Movement, and the progression of this struggle in the Netherlands finally culminated in this occupation and the unity of several organizations.

Among those involved where the Spinhuis Collective, Humanities Rallies, and students from The Free University (VU), Utrecht, UvA Science department, and Amsterdam University College. On the same day, the Humanities Rallies held a demonstration march that went past the Bungehuis. After this, people from the humanities demonstration joined the occupation. The university asked the occupiers to move to an empty building, to diminish their impact, along with writing a letter at 3:30pm with the names of four people who would be sued and held personally responsible for any damages and charged with breaking and entering. One of the four students in the letter was not actually in the country during the occupation.

Among those involved where the Spinhuis Collective, Humanities Rallies, and students from The Free University (VU), Utrecht, UvA Science department, and Amsterdam University College. On the same day, the Humanities Rallies held a demonstration march that went past the Bungehuis. After this, people from the humanities demonstration joined the occupation. The university asked the occupiers to move to an empty building, to diminish their impact, along with writing a letter at 3:30pm with the names of four people who would be sued and held personally responsible for any damages and charged with breaking and entering. One of the four students in the letter was not actually in the country during the occupation.

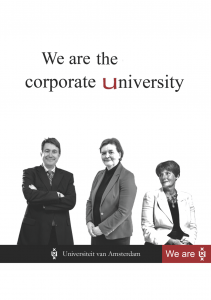

Ironically UvA launched a campaign in the last year named “we are u” in order to attract more students by promoting the idea of intellectual rebels who are always questioning, but their response to the occupation and to the movements that lead to it show they are not as welcoming to actions that stem from such questioning. The university administration approached the police about pressing charges of breaking and entering against the occupiers. A court case was scheduled for Thursday 19 February where the university would be suing for 100,000 euros per day per person for those remaining in the building after this date.

This movement was the creation of the unity of several action groups; some which originate in the fight against the UvA and VU merger. The first proposed plans of the merger of the two universities’ science departments were voted down in December 2013 by the central student and staff council. Six months later and an email that was sent to the central student council that still included the original merger plan, along with housing plans, was leaked by uvaleaks.nl. By the end of the week, students occupied the service center of the science park until they were allowed to speak with the board about the continued negotiations of the merger.

In the first round of talks between the board and the students, the head of the University claimed that the student union and the departmental student and staff councils had agreed on the path of the merger. However, two of the students in the talk were on the student council, along with other sources who claimed that these organizations were not aware of any agreement.

The occupation continued through the weekend, and on that Monday in a second meeting, three demands were promised and signed. These stated that students would be allowed to sit in all department board meetings, an email with the time path and situation of the merger would be sent out to the department within the next few months, and that the student council would have voting rights in regard to the timeline and negotiations. These demands were never met.

Following this, the university announced a 10% cut of the Humanities department budget and the implementation of previously announced housing changes. These changes would relocate the humanities faculties to another building with a newly added extension. However, when asked to move, the extension was not finished, yet the university still closed some of the old rooms such as the humanities common room.

In response a group of students turned the old common room, Spinhuis, into a squat. The promised new common room, which was unfinished, would be turned into a university run center instead of student run. So, the squatters known as the Spinhuis Collective opened it back up to students, selling coffee and toasties and hosting student activities.

In response to this, the UvA pressed charges, asking for 100,000 euros per day that they stayed in the building after the court case. After winning the first two court cases, the Spinhuis Collective were evicted after four months after the third court case. The university then proceeded to sue 10 students, 5 of whom were not actually affiliated with the Spinhuis Collective. Therefore, including the most recent occupation, the university is guilty of misidentification of those involved on two separate occasions, demonstrating a degree of carelessness in the handling of student protestations.

After this the action groups Humanities Rallies, UvA leaks, Science Park Occupiers, Debt Generation Against Student Financing Cuts, and Spinhuis Collective joined together to create the New University (newuni.nl) and this new group planned the current occupation.

Support for the occupation came in several forms. The occupation was visited by national politicians on Monday and Friday, as well as Freek de Jonge, a famous Dutch comedian. The Democratic Party and Socialist Party offered a general petition to the board of directors with 3,700 signatures. The youth department of the Green Party spoke out in support along with the general left winged trade union and several academic departments and student organization. 36 staff members also spoke out in support of the occupation and their demands, along with the 82 members of staff and 18 external employees who signed an open letter, stating that the fines being asked by the university were outrageous and that they had been in the building or planned to be at some point during the occupation and should also be fined alongside the student participants.

Another remarkable example of employee solidarity with the movement was a 61 year old professor who joined the occupation and was given the only mattress in the building. He declared that he had been waiting 30 years for students to do something like this, but that he was also afraid of losing his job. The university had already announced that no employees were allowed inside the occupation, even though the students were allowing people in for research and educational purposes. This all occurred within the first six days, which made it longer than the occupation in 1969 that brought about the democratic process within the university and whose demands shared similarities with the current demands.

Another remarkable example of employee solidarity with the movement was a 61 year old professor who joined the occupation and was given the only mattress in the building. He declared that he had been waiting 30 years for students to do something like this, but that he was also afraid of losing his job. The university had already announced that no employees were allowed inside the occupation, even though the students were allowing people in for research and educational purposes. This all occurred within the first six days, which made it longer than the occupation in 1969 that brought about the democratic process within the university and whose demands shared similarities with the current demands.

The movement has demanded:

- Democratic elections of the university board.

- Change of how finance is allocated, to be based on input instead of return value.

- Cancellation of the 2016/2017 humanities department profile, that will combines language departments into one European studies degree and that requires an average of 20 students per class.

- Referendums within departments and programs in regard to the merger of UvA and VU

- Fixed contracts for staff appointments to encourage participation in the democratic process without fear of losing their jobs.

- Open debate about housing cost in relation to budget cuts in research and education in reference to the university’s mother corporation, UvA Holdings which essentially a real-estate corporation.

The university refused to meet with the students and discuss these demands unless they first left the occupation. A local news station offered to host the debate. The occupiers accepted, but the university refused once again. Criticism came from politicians and organizations about the unwillingness of the university to discuss these issues.

In the court case on Thursday the court ruled that the occupation would be evicted and fined 1,000 euros per day that they remained in the building. However, the mayor postponed the eviction to host a talk between the students and the board of the university. Despite this, the university was not willing to adhere to any demands directly. They only promised more talks and debates that would not allow for voting rights; much like they had in the previous movements where the demands promised did not come to fruition.

After the ruling of the court case the occupation announced that anyone who wanted to leave could and any who wanted to stay could. Among those who stayed was the 61 year old professor. The Humanities Department staff council bought the ladder used to get in and out of the occupation to cover the first day’s fines. The Socialist Party met with them on the second day and bought a pamphlet of their demands to show to the Ministry of Education and to cover the second day’s fines. They even brought these issues to parliament, but no response has yet been given yet. Lastly, the Student Union announced they would cover the legal fees incurred by the court case.

During the eviction, students were arrest one by one while a crowd of about 100 people waited outside in support. Some of the students who were arrested were only sitting down outside, refusing to move for police. Another student who was outside had his ankle trampled by a police horse. Three students were released from jail that evening, but the rest were held until at least the next day.

After the eviction the crowd grew and continued to march to the main administrative building of the university, Maagdenhuis, with riot police following in their vans to monitor the demonstrators. Also, a noise demonstration was held outside of the police station in solidarity with those whom were arrested. A national general assembly had been planned for that day in the university’s library, but security refused the students access and cancelled their room booking. Upon entering another building, after more difficulties, the police were called, but eventually the university reluctantly allowed them to remain.

Since the eviction, notable figures such as Noam Chomsky and Judith Butler have signed the student’s petition in support of the movement and their demands. Multiple UK student groups along with some in Barcelona have spoken out in solidarity.

One of the students released on Wednesday 25 February reported discrimination and brutality in the handling of certain students in custody. This is demonstrated by the case of a police officer dragging a girl into the elevator by her hair during the eviction one source has reported. While in jail overnight, students were not allowed access to medications nor were they allowed to seek legal advice. As of 5:00pm on Wednesday all of the students were released from jail.

A protest was scheduled for Wednesday that attracted even more support as this movement has gained national and international attention. Around 1,700 people marched to the Maagdenhuis where speeches were given by the Socialist Party and the 61 year old professor among others. Toward the end of the demonstration around 400 protestors entered the Maagdenhuis by force to hold a general assembly. During this assembly the head of the board and the mayor of Amsterdam came to speak to the students. Yet again, nothing was achieved. A small group of students continued to occupy the Maagdenhuis through the night. On Thursday 28 February the university conceded that they would allow a student to sit on the board and to hold off any cuts to the humanities for at least two years. There are still debates on if this is enough or if they should keep pushing while they have momentum to gain their main demand, democracy.

A protest was scheduled for Wednesday that attracted even more support as this movement has gained national and international attention. Around 1,700 people marched to the Maagdenhuis where speeches were given by the Socialist Party and the 61 year old professor among others. Toward the end of the demonstration around 400 protestors entered the Maagdenhuis by force to hold a general assembly. During this assembly the head of the board and the mayor of Amsterdam came to speak to the students. Yet again, nothing was achieved. A small group of students continued to occupy the Maagdenhuis through the night. On Thursday 28 February the university conceded that they would allow a student to sit on the board and to hold off any cuts to the humanities for at least two years. There are still debates on if this is enough or if they should keep pushing while they have momentum to gain their main demand, democracy.

The university’s lack of willingness to discuss the wants and demands of several student movements and this most recent occupation, have put the issue of the privatization of universities on the international stage. Such issues have already been raised in regards to the free education movement, the potential privatization of museums such as the National Gallery in London, solidarity from other student organizations, and the international student outcry to end market thinking in universities.

by Danielle Anderson, KCL Marxists