The last day of the NUS national conference saw intense factional fighting over a democratic reform motion, capping off an intensely divided conference. After speeches decrying the underhanded and at times aggressive tactics of campaigners, including personal attacks and racism, as well as an impassioned warning against depoliticisation, conference discussed a motion that aimed at a full overhaul of the democratic structures of the NUS.

This included:

- The move from STV to a complicated “Borda” system which makes it less likely for divisive candidates to be chosen, privileging those who provoke less disagreement and have more 2nd place votes, thus seeking to select the least-disliked, lowest-common denominator candidates, who become more likely to win if they strip any contentious content from their programmes. This complicated system enables far more bureaucratic manipulation of the democratic process for those in the know of how it works. An amendment to remove this change passed, meaning NUS remains with STV.

- Introducing a post conference online ballot, as well as more online voting, to take focus away from discussion and debate at conference, where democratically elected delegates are mandated to be in one room hearing the arguments, to votes away from conference, where those in the know who dedicate time all year round to the bureaucracy, who know when deadlines and votes are taking place etc, will have an undue influence. Amendment against this was debated, fell.

- On online process in which SUs can register dissatisfaction with an elected officer, and if 10% agree then it forces a vote of no confidence, allowing a minority to unseat officers they don’t like, especially under the influence of public media attacks in the press.

- To remove the democratically elected so-called block of 15 in the NEC completely, which hold officers to account throughout the year, (which would apparently no longer be needed due to the online accountability process). The NEC becomes mainly for full-time officers to make quick decisions between conferences, is removed of its policy role, while the number of elected positions is dramatically decreased.

- To replace the chair of conference with a “neutral” student recruited by DPC to facilitate, while DPC (democratic procedural committee) make decisions re democratic process i.e. counts. In reality all students have opinions and can be recruited by factions.

- A pre-conference ballot to identify “consensual” motions allowing 2 thirds to pass motions without debate.

- To commit to a regional, decentralised and federal decision making and to reduce the role of national NUS structures.

Overall this debate saw incredibly underhanded and bureaucratic tactics from the right. The original motion was developed by an unelected taskforce and seeks to remove democratic debate and discussion and increase the influence of hacks and bureaucratic wrangling, contributing to the attempted depoliticisation of the NUS, to stop it from fighting on political issues which affect students. The bureaucratic attempts to force this motion through without amendment were shocking. It supporters claimed they had consensus, that this would increase participation for all students, reduce factionalism and modernise the democracy.

Yet they succeeded to block most amendments (of which there were many, showing the discontent around this motion) from being discussed at all, by procedural motion. Procedural motions piled on as many of no confidence in the chair, and much filibustering ensued. Speakers accused the right of calling round during the night to make backroom deals, and staff with no right of reply were attacked on twitter.

Ultimately the motion was passed with only one amendment. The right claimed the motion was to increase openness, and that its opponents were a minority who wanted “more of the same” but the opposite was true, as those who knew procedure blocked discussion on what was the biggest democratic overhaul since 1922.

This represented an incredibly coordinated campaign on the behalf of the right to dramatically impinge upon the politicisation and leftward shift that has been taking place in the NUS. Winning most positions and watering down bold motions, they mounted a strategic campaign to maintain their grip while paying lip-service to the radical ideas which were undoubtedly popular among students and delegates. The passage of this motion will unfortunately harm attempts to move the NUS into fighting struggle against government attacks.

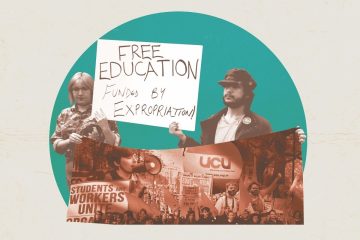

Malia Bouattia closed the conference in a tearful speech which emphasised her efforts to fight for transformation, for links to the labour movement, for liberation from racism and sexism, for free education (and all that entails) and for freedom for Palestine. She drew attention to the attacks and harassment she had faced while in office, from racism and from those furious at a president who attempted to change the game.

However it must be recognised that the win for the right was partly a result of the lack of resolve on the part of the left leadership when in office, who failed to demonstrate the power of a union of students and teachers to win real political change on a socialist basis. The right was therefore able to characterise the left as irrelevant and uninvolved, shouting from the sidelines, while they “got things done” in the corridors of power, undercutting the left arguments by preaching the same ideals but adding a commitment to “realistic” institutional work to soften government attacks.

This struck an attractive tone for many delegates. The Blairites and the anti-NUS conservative student’s platforms fed into each other as both stoked student concerns over a “broken” NUS throughout the year. The Blairites pointed to the disaffiliation campaigns and placed themselves as the only ones able to halt this move, by policies that spoke to “actual students”, and abandoned “divisive” and “irrelevant” radical politics. The left such as NCAFC on the other hand made good interventions, arguing for a politicised NUS and proposing radical ideals of universal free education, yet were unprepared to beat the coordinated strategy of the right, which really won on the strength of its delegate election campaigns in unis throughout the year.

Furthermore, their emphasis on protests and direct action, whilst important, failed to articulate a positive alternative to austerity that could be fought for and achieved. They could have gained credibility by linking to a wider struggle for political power, to link up with the labour party and other unions to unseat the tories and institute socialist policy.

They argued for uncompromising ideals, but didn’t explain enough how the watering down of those ideals to attempt “realistic” changes to government policy was not only an unfortunate shortcoming of principle, but a barrier to even the achievement of limited reforms. They called for a tax on the rich when they should be calling for workers control of industry. They called for universal living grants and free education (as policy) rather than nationalised housing, democratically controlled universities, instituted by a socialist organisation capable of instituting a programme to get rid of capitalists, not just disrupting them by direct action to get government to change policy. Despite their radicalism they were thus in reality just reformists.

Only a bold socialist programme, linking the student movement to the labour movement, can articulate a credible alternative to the choice between high ideals and crushing austerity, by explaining how we can deliver on these promises and why capitalism cannot.