Recently the University of Warwick announced that it would implement a new scheme for disadvantaged students from around the West Midlands region. The scheme, named “Warwick Scholars’, would cost £10 million a year and is aimed at improving the admissions prospects of talented students who live in deprived areas or are from disadvantaged groups (i.e. people in local authority care, on free school meals, having a long-term illness, etc). This is by no means insignificant. £10 million is close to a fifth of the university’s annual income as of 2017-2018 (the total figure was £56 million).

Stuart Croft, vice-chancellor of the university, announced that among the measures being introduced, there would be a reduction in the entry requirements for A-level students by as much as four grades. Furthermore, students enrolled in the scheme will see their tuition fees reduced by half, and will receive a means-tested support bursary with £2,000 a year. This is on top of other bursaries which students will be eligible for.

This move is not nearly as selfless or charitable as it may appear. The university management has its own vested interests for doing so. Recently, the university has suffered a serious image problem with regards to the group chat scandal, which has likely reduced the attraction of prospective students to that university. Moreover, with the possibility of Brexit in the not-too-distant future, the university fears losing a lucrative source of income in the form of tuition fees from foreign students, as it becomes harder for EU students to come to the UK to live and study.

Far from being the benevolent, philanthropic measure that it is being presented as, it is a cold calculation by a panicking higher management, desperate to find a way of maintaining, and even increasing, its source of income. With universities increasingly being run as businesses as a result of marketisation, these measures are clearly designed at maximising the number of potential “consumers” in the form of students, but not so much at improving the quality of education as it currently exists.

Evidence that this is effectively very much driven by corporate concerns is given by Croft himself:

“In our region we are not successful enough at supporting young people with talent. When they are successful, we lose far too many of those students to London. So one of the things we want to do is try to help build a cohort of people who succeed and stay in the region, and contribute to its social and economic success.”

The grievance of Croft and the university management is that talented students that could be contributing their income to the University of Warwick are instead moving to the more promising capital, where there are far more opportunities for lucrative employment.

As generous as the university’s measures to help disadvantaged students may be, they do not come close to solving the structural issues behind the inability of young people from disadvantaged backgrounds to go to prestigious universities like Oxford, Cambridge and Warwick. After all, the university’s scheme doesn’t say anything about how it intends to help those who are not lucky enough to fall under its definition of “talented students”, meaning, at best, only a few thousand people will benefit out of the millions of deprived young people that exist across the country.

Statistics show that even in primary school, the gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers in terms of literacy, reading and maths is significant. This gap remains in place all through secondary school, by the end of which, the most disadvantaged students are two years of learning behind their peers.

Meanwhile, a recent Ipsos Mori poll found that the proportion of pupils from “low affluence” households who see themselves going to university has decreased due to the increase in tuition fees.

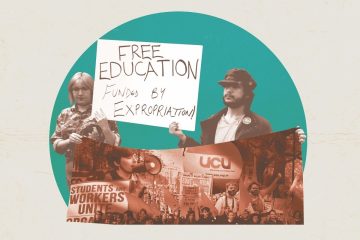

Instead of spending money on helping a handful of individual students from disadvantaged backgrounds, what is needed is a publicly-funded National Education Service, a proposal which has been put forward by the Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn. This will involve bringing all universities in-house and rolling back all privatisation in its entirety, along with a reversal of all the cuts made to education in recent years. It will involve eliminating tuition fees and making university free for all, as well as allowing mature students to return to higher education at any point during their lives, without having to worry about paying a fortune. This should be done in conjunction with a complete reversal of all the other forms of austerity that have plunged so many young people into a state of deprivation. We need free education, funded by expropriation.

Generous schemes like those being put forward by Warwick and now Oxford, only serve as sticking plaster on an inherently broken education system. These universities, which are effectively corporations, cannot be relied upon to fund opportunities for young people. This is something which they will only consider doing if it enhances their profit margins. Should such schemes fail to do so, they will most likely be abandoned. Moreover, they continue to waste millions upon shiny new buildings, corporate schemes and vice-chancellor’s salaries that are of no benefit whatsoever to students, but make plenty of money for a few greedy individuals. What is needed, then, is the election of a Corbyn-led Labour government on a socialist programme.

Aaron Kyereh-Mireku , Warwick Marxist Society

0 Comments