This month, hundreds of thousands of students are expected to head to universities across the UK. However, the Universities and Colleges Union (UCU) recently warned that this could cause a “public health crisis”, adding that we are weeks away from “sleepwalking into disaster”.

Under the current plans – which vary between institutions – universities will be combining face-to-face and online teaching. Whilst some institutions, including Cambridge, have announced that all teaching for the academic year will be delivered online, most will be providing some form of face-to-face interaction.

In a recent interview with the Observer, UCU general secretary, Jo Grady, said that close to a million students moving from all corners of the country into halls of residence and “congregat[ing] in large numbers” could lead to universities being the “care homes of any second wave of Covid”.

It’s not just academic staff who are concerned about the prospect of universities reopening: students and their parents are anxious too. Universities are already known as being a breeding ground for diseases, with ‘freshers’ flu’ often joked as being a first-semester rite of passage.

Meanwhile, Labour shadow minister for universities, Emma Hardy, accused the government of neglecting universities and letting them deal with the problem themselves. The Tories’ shambolic handling of the coronavirus crisis is ample cause for concern, and the recent reopening of schools which the government has bulldozed through has only added fuel to the fire.

In the United States, where many students have already returned to their universities, thousands of coronavirus cases have been linked back to campuses. There is also the danger that many students attending universities will have come from newly-announced ‘Covid hotspots‘, including Birmingham and Leeds.

The UCU does not want students to return to campuses until Christmas unless universities implement stringent testing programmes. According to Grady, “there are no plans for universal testing on campus, or even for everybody who moves out of a lockdown zone to be tested before they’re allowed to go to university”.

It is not just students and staff who would be put at risk by this reckless rush back to campus – wider communities would also be put in danger by increased infection rates. Students flock to pubs and shopping centres during freshers’ week; understandably, they don’t want to spend their whole semester cooped up in their rooms.

No doubt the Tories will use this as a scapegoat to deflect the blame if there are flare-ups in university cities. This would be in spite of their concerted efforts to get people back into pubs and restaurants with the ‘Eat Out To Help Out’ scheme.

It’s no surprise that universities are keen to get students back to campus, given that many institutions are struggling financially. With an inevitable drop in overseas students – who can pay up to three times as much as British students – universities are set to face serious financial problems.

University workers have already seen their working conditions worsen considerably over the past few years, with this year’s strike action drawing attention to inequality in the workplace and casualisation forcing staff into precarious situations. A return to work in unsafe conditions represents a continuation of this decline in standards.

As such, it’s important that the UCU links this current debacle with its previous struggles. The coronavirus crisis may be an unforeseen, accidental factor, but the way that university managers are dealing with it is far from surprising. After all, they won’t be the ones delivering face-to-face teaching.

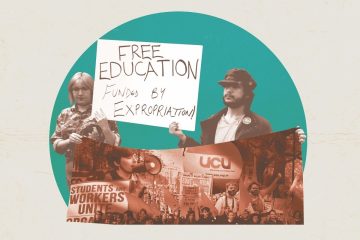

The UCU should look to the recent A-Level protests as an example of what can be achieved with bold, militant action. Students took to the streets in protest against the discriminatory grading system, forcing the government into a u-turn in less than a week. If this is what can be achieved with a few days of last-minute demonstrations, imagine what could be achieved if the UCU threw their weight behind a coordinated, national campaign, reaching out to the wider Labour movement.

Student groups and societies should offer support to their local UCU branches, and coordinate joint actions to pressure both the government and university management into ensuring that campuses are safe. If demands for stringent safety measures and improved working conditions aren’t met, UCU branches should take matters into their own hands by organising health and safety committees to carry out such measures themselves. After all, who knows how to run workplaces better than the workers themselves?

Moreover, we must demand that the government makes up the loss of funding that universities face, so that universities have the funds to implement safety measures without cutting corners. The financial crisis facing universities has revealed what we already knew – that profiteering does not belong in our education. If the coronavirus is causing universities to go bankrupt, then we should demand the nationalisation of the education system outright. That way, we can run universities in the interests of need and not profit.

The Marxist Student Federation will give its full support to any action that will ensure the safety of staff and students. Join us in the fight for a free and fair education system!

Emma Stanhope, UEA Marxists